Alexander Pierce used to live on top of the world.

His last name gleamed in steel and glass, crowning buildings that cut the sky like razor blades. From immaculate boardrooms to champagne-soaked charity dinners and calculated speeches, his life was built on control. Nothing moved without his permission. No problem lasted more than two calls. No “no” survived the next morning.

Until the rainy night.

It was a return home that couldn’t have lasted more than fifteen minutes. Shining asphalt, traffic lights breathing red, green, yellow. A distracted driver. An instant split in two. Glass exploding into tiny sparks. Metal groaning like a wounded animal. Silence. And then nothingness, black, deep, smelling of gasoline.

He woke up days later, as if shipwrecked in a body he didn’t recognize. The doctors spoke cautiously, words measured as if they could cut him: “Let’s wait…”, “We’ll watch…”, “It’s early…” But weeks turned into months, and hope began to seem like an impolite visit: it entered without knocking, promised to stay, and always left before dawn. The sentence fell under the cold light of a consulting room:

—The nerve damage is permanent, Mr. Pierce. You’ll never walk again.

The words didn’t pierce him: they covered him, like a layer of fresh cement. He left the hospital in a wheelchair that felt more like a prison than a vehicle. He avoided looking at his reflection; each piece of glass returned a stranger to him. He canceled dinners, delegated meetings, and locked himself in his penthouse overlooking a horizon that no longer meant anything. His fortune, suddenly, was a useless object in a display case: expensive, shiny, and absolutely incapable of buying the one thing he desired.

That day, for no clear reason, he asked his driver to drop him off at the city park. Maybe he needed air that hadn’t passed through silent filters. The leaves rustled overhead. Children chased bubbles. Alexander was thinking about nothing—or pretending to—when the phone slipped from his lap and hit the pavement.

He bent down to reach it. He knew it might tip over if he pushed any harder. He bit back a curse.

-Take.

A small, brown hand offered him the phone as casually as someone returning a ball. The girl couldn’t have been more than seven years old. She was wearing faded denim overalls over a beige T-shirt; her knees were scraped, her sneakers were frayed. But her eyes… Her eyes didn’t waver. She looked at him as if she’d seen him before, behind everything.

“Thank you,” he said dryly.

She didn’t leave. She watched him with an attention that was both uncomfortable and reassuring.

“Why are you in that chair?” he asked without a hint of shame.

Alexander almost found it funny. The adults skirted the subject like a well; the children didn’t.

“Because I can’t walk. And I won’t,” he replied. His tone came out harsh.

—Who says so?

—The doctors. —The word fell like a stone.

She tilted her head.

—And you believe them?

It was an absurd pang. Alexander was fed up with being asked to “think positively,” with being sold miracles wrapped in science. But that wasn’t empty advice. It sounded like a challenge. In the stubborn gleam of her eyes, he recognized something that had once been his: that way of biting into impossibility and not letting go.

Impulsiveness—or tiredness, or curiosity—pushed him on.

“If you cure me… I’ll adopt you,” he said, like someone throwing a coin into a fountain and expecting nothing.

There was no discreet giggle. There was no glance toward the sky. There were no steps back. The girl nodded simply.

-Alright.

Alexander blinked. For a second, the park disappeared. Only the line of his mouth remained, firm, and that yes, unadorned, like an invisible contract.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

—Amara.

—Alexander.

“Tomorrow. Same place,” he said, turning on his heel. He left with his shoulders squared, small, as if entering a battle he already knew.

That night, with the city spread out beneath his window like a lighting board, Alexander replayed the scene over and over again. The absurd promise. The sparkle in Amara’s eyes. And a timid, irritating thought: maybe he shouldn’t underestimate her.

He didn’t believe in miracles. He’d tried it when spinal cord inflammation was still a manageable word and therapists spoke in “maybes” rather than “never.” But those were days of archaeology. So when Amara showed up the next morning with a plastic bag and a stack of photocopies, he hoped he was wasting his time.

“We start here,” she said, pulling out mismatched, thrift-store-scented resistance bands. She strapped one around his forearms with a surgeon’s focus. “Stronger arms, stronger back. Stronger back, stronger core. If your core holds up, your legs will start listening.”

“I’ve seen the best,” he snorted. “Nothing works.”

“Then let’s try what you haven’t done,” he concluded, and began counting. “One. Two. That one doesn’t count, repeat. Three. Four…”

The first few days, Alexander obeyed her to please her, as if it were a visit and not a plan. She didn’t argue: she gave small orders and celebrated small victories. She repeated, corrected, insisted. On Saturdays, he showed up with printed articles from the library: experimental therapies, studies on neuroplasticity, adapted yoga exercises that seemed like a joke until, suddenly, they weren’t. He told her about a community center two blocks away. About a retired trainer who, she said, “listens to me when I insist.”

He took it one afternoon. The Center resembled everything Alexander had dismissed without looking: peeling paint, motivational posters with crooked edges, volunteers with smiles that seemed bigger than their paychecks. In the main room, a tall man with gray hair was applying tape to a parallel bar. He had the hands of someone who understood the inside of the body.

“Pierce, right?” His voice was deep, warm. “It’s Rivera. Amara told me about you. Weeks ago.”

Alexander looked at the girl, who shrugged, not at all guilty.

“Your legs might not be dead,” Rivera said, bending down to examine their posture. “Maybe they need a war to wake them up.”

There were no sweet promises. No one said “tomorrow.” Rivera showed him the arsenal: parallel bars, harnesses, a treadmill, a partially weight-relieved treadmill, electrodes. “We’re going to trick your brain into remembering,” he explained. “We’re going to make movements so small they’ll make you mad. And you’ll get as tired as if you’d just climbed a mountain.”

The first session left him drenched. Sweat on the back of his neck, trembling in his elbows, an unfamiliar tingling in the sole of his right foot that both frightened and excited him. Sometimes, in front of a mirror, they practiced the simple act of straightening their backs. “Higher up the sternum,” Rivera would say. “Breathe as if your rib were a blind.” Amara applauded every inch gained as if it were a kilometer.

Alexander began to leave the penthouse with gusto. One hour a day turned into two. Then three. He discovered it was possible to be fed up with oneself and still keep going. He discovered that pain could mean progress, not punishment. He discovered that when Amara counted quietly—“seven, eight, nine”—that rhythm gave him a place to return to.

The little girl never missed a day. After school, her uniform wrinkled and her hair in new braids, she would show up with her torn notebook—AMARA written in marker—and a list of “fix-it ideas.” Alexander learned, over time, that she didn’t have a mother. That she lived with an aunt who worked endless hours cleaning offices. That the park was her playground and the library her refuge. That she sometimes drew devices: pulleys with colored knots, bars resting on blocks, notes in the margin: “this might help,” “ask Rivera.” He knew that when an adult told her “never,” she would clench her jaw and jot down, in a corner, the forbidden word as if it were an enemy to be defeated.

The bad days also arrived. Spasms that seemed like mockery of the body. A slip between the bars that ended with a thud and an even worse silence on the floor. Alexander looked at the ceiling and thought: “That’s it.” Amara, her thin voice trembling, held his hand.

“We’re not going to let the floor win,” he whispered. “Not today, not tomorrow.”

Rivera, serious, explained the limits, the risks, the cold, hard numbers from the studies. And yet, he re-tied him to the harness and said, “Up. Again.”

Months passed like persistent drops. The muscles in his torso became firm. His shoulders, a barbell of their own. One day, in front of the Center’s smudged mirror, Alexander saw something small: the toes on his left foot gave a start. No one breathed. Amara broke the silence with a scream that made even those who didn’t know what it was about laugh.

“Did you see it?” he said, jumping. “They’re listening!”

The day of the first miracle—if it had to be called that—was spring. Clear light streamed in through the high windows, dust dancing in the air. Rivera adjusted the bars. Amara stood at the end, arms crossed, that defiant half-smile.

“Weight on your arms. Engage your core. On my signal, lock your knees,” Rivera instructed.

Alexander clenched his hands until he felt the marks of the metal. His entire body vibrated: effort, fear, memory. And then, like a door that gives way after thousands of silent attempts, his knees obeyed. Not perfectly. Not by much. But they obeyed.

I was standing.

The tremors shot up his legs like lightning. His eyes burned, and he didn’t know if it was from the sweat or something else, something he didn’t want to name. Ten seconds. Twelve. Fifteen. Rivera counted, Amara smiled silently, as if keeping a secret. When he returned to his chair, Alexander was trembling all over, but his mind… his mind was a clear sky.

The doctors hadn’t lied. The damage was there, it was still there. Only no one had calculated the stubbornness of three people engaged in a long war: science and stubbornness, discipline, and a girl who, no matter how much the world repeated it, couldn’t say “never.”

The following months were a map of minimal progress that, when added together, seemed like a new landscape. From bars to forearm crutches. From crutches to tentative steps inside the house, under the fierce gaze of a young physical therapist Rivera brought in one afternoon to expand the team. Alexander, who had measured his life in contracts and towers, began to measure it in repetitions and degrees of flexion.

Meanwhile, the promise grew like a plant on the windowsill. “If you cure me, I’ll adopt you.” It sounded ridiculous spoken aloud, yet it took on a seriousness that moved him. It wasn’t charity or payment. It was recognition. Gratitude in the form of a home.

He spoke to his lawyer. He spoke to a sleepy-eyed social worker who asked pointed questions:

—Why do you want to adopt this girl, Mr. Pierce?

“Because he gave me back something no one else could,” she replied. “And because I don’t want him to depend on his luck running into strangers in parks for the rest of his life.”

The woman looked at him for a long time, as if trying to see if there were any cracks. And of course there were. But there was also a new truth in the way Alexander breathed and looked at the world.

Amara heard the word “adoption” by accident one afternoon when he thought she was in the living room while he was talking to the lawyer in the kitchen. That night, she, seemingly invincible, approached him and asked bluntly:

—Are you going to love me even if you’re not completely cured?

The question hit her hard. How many times had life imposed conditions on that girl? “If you behave, if you get good grades, if you stay out of trouble…” He cupped her face in his hands.

—Amara, I said something stupid the first day. A challenge. You cured something else before my legs. You pulled me out of the hole I was digging myself into. That’s not measured in steps. It doesn’t depend on whether I run or not. I want you here. Period.

She nodded once, slowly. Then she breathed, and it was as if an invisible string had loosened.

The first unaided walk—barely a step, his right foot advancing tentatively—didn’t happen in the Center or in front of a doctor. It happened at dusk, in the same park. The sky was an orange canvas; a man was walking a dog, looking philosophical. Alexander let go of his left crutch for a second. A second and a half. Two. And he moved forward. Amara was at his side, her hands in the pockets of the overalls that were already too short for him.

“Look at us,” he said, without fanfare. “At first it was impossible. Now it’s… this.”

They celebrated with melted ice cream. They called Rivera to tell him about it, laughing. Upon returning to the penthouse—no longer a cage, but a possible place—Amara drew a tiny step in her notebook with arrows and the caption: “Don’t forget this happened.”

The adoption was, like everything in real life, a combination of paperwork, awkward interviews, and waiting. Alexander learned the name of the social worker, the color of the judge’s coat, and the strange rhythms of the courtroom. He discovered that money accelerated some things and left others alone. He discovered that his last name, which had once opened doors with a hiss, now required sitting back while others decided. And he accepted. For the first time, accepting didn’t feel like defeat, but rather humility.

Amara decorated what would become her room with magazine clippings, drawings, and a world map with threads connecting cities to ideas: “Tokyo — robots that help you walk”; “Lima — a guy at the library said there are good engineers”; “Nairobi — a woman who fixes chairs.” On the desk, she placed her notebook with a title on the back page: “Fix: Things You Can Do.”

The final signature arrived on a clear morning, one of those that smells of bread. In the courtroom, the echo made the words more formal than necessary. The judge, tired and kind, looked up.

—Mr. Pierce, do you confirm your intention to adopt Amara…?

-Yeah.

—Amara, do you agree?

“I more than agree,” she said, with that seriousness of hers that made others smile.

There was a blurry photo taken by a secretary in a hurry. There were tears. There was a strange, full silence as they stepped outside. Alexander placed his hand on his daughter’s shoulder—his daughter—for a moment and felt that the world, at last, had just the right weight.

That night, on the threshold of the new room, he stood for a moment leaning on his cane. Amara was arranging books on the shelf: first aid manuals, stories, an old encyclopedia from the library that she planned to return “tomorrow, tomorrow.” On the desk, the notebook was open. On the back page, in cramped handwriting, it said: “Alex’s legs: fixed.” Below, in smaller text: “Alex’s life: under repair, but almost there.”

“You didn’t just help me walk,” he said slowly, so as not to break anything. “You gave me back my life.”

Amara smiled over her shoulder, as if she had known before he said it.

“And you gave me mine,” he replied. “That was part of the deal, wasn’t it?”

They laughed. The word “never” had been banished from their home for months, and none of them seemed to miss it.

A year later, the city was still the same, and yet it was different when they looked at it together. Alexander patiently descended short stairs. Sometimes, he walked without a cane from the elevator to the entrance of the Center. Rivera, with whiter hair and the same craftsman’s gaze, greeted him with a handshake that resembled a medal.

“Look at you, Pierce,” he said. “I didn’t promise anything, and look, it happened anyway.”

“It wasn’t a miracle,” Alexander replied, without drama. “It was work. And it was her.”

Amara had grown an inch and a whole world. She kept her braids, but now she liked to decorate them with colorful threads she wove herself. Her ideas for “fixing” had become more sophisticated: sketches of homemade exoskeletons made from PVC pipes, small notes in the margins about levers, pulleys, and proportions. One Saturday, they arrived at the park with a heavy backpack: inside, a simple harness and a rope they had first tested in the penthouse hallway. Alexander made progress with this invention—ugly, useful—and they laughed when they discovered it was possible to play again.

They returned to the courthouse, but this time to accompany another child from the Center, a quiet boy who had befriended Amara and was now going to live with a young couple. Alexander found himself moved by stories that weren’t his own, by endings that opened new beginnings. There was ice cream for everyone and a philosophical discussion, afterward, about whether lemon sorbet counts as real ice cream.

The Pierce Towers continued to shine on the skyline, unfamiliar and identical. Alexander began going to the office a couple of days a week. He entered without pomp. He sat down, asked questions, delegated without the pride he once mistook for certainty. On the office walls, next to the photos of glamorous openings, he hung a new one: him, on parallel bars, sweaty and laughing; on one side, Rivera with tape on his hands; on the other, Amara with her open notebook. He placed it at eye level to remind himself—every day—where the important things begin.

One Sunday, they returned to the park they’d used the first time. Alexander’s phone—older, with a scratch on the corner that Amara refused to cover with a case—was snug in his pocket. They sat under the same tree. People passed by, unpredictable and wonderful: a woman running with headphones, a child dragging a balloon, an old man feeding doves with the solemnity of a priest.

—If you hadn’t dropped the phone… —Amara began.

“If you hadn’t picked it up,” he finished.

They looked at each other with a recognition that no longer needed words. Sometimes, life changed for no reason. Sometimes, it changed because someone, small and stubborn, decided things could be different.

“Dad,” she said then, testing the word like a new candy. “Today I want to learn how to fix something I don’t know how to fix.”

Alexander straightened up. That “daddy” fixed something inside him that he didn’t even know was broken.

-What thing?

Amara pointed at the world with her hand, stretching from the tree trunk to the last glass tower.

—Whatever is left.

And just like that, they stood up. They walked slowly along the path. The cane tapped the earth with its own sure rhythm. The sun moved a little. A girl with a pink bow bumped into Amara and apologized hastily. Amara winked at her and tossed a bouncy ball back.

They didn’t believe in “never.” They believed in “not yet.” In “we’ll see.” In “another time.” Because the promise of the park, which had begun as an absurd challenge, had demonstrated something simple and fierce: there are priests who don’t have gowns or scalpels, and yet they restore the pulse. There are adoptions that begin before the paperwork is even filed, when two lonely people recognize each other and decide to team up. There are days that, without warning, change the entire map.

Life was never the same again. It was better, more honest. With ugly harnesses that worked, with falls that didn’t dictate the end, with notebooks full of plans that seemed impossible until they weren’t. On the last page of Amara’s notebook, next to the old “Alex’s Legs: Fixed,” appeared one more line, written in fresh ink:

“The word ‘never’ means retired.

Its substitute is ‘still’.”

And below, in large, round letters, like a girl who has learned to name her world:

“Family: at home.”

News

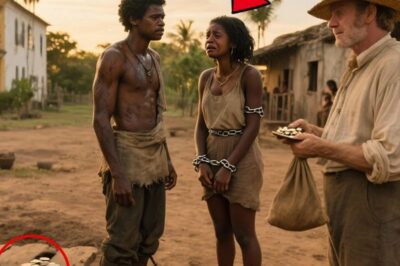

La ama ordenó que arrojaran al bebé del esclavo al río… pero 18 años después regresó y sucedió algo impactante…

La noche en Maranhão envolvió a São Luís con su calor húmedo y sofocante, mientras las estrellas atestiguaban en silencio…

La esclava vio a la ama besando al sacerdote… ¡pero lo que ella contó años después escandalizó a todo el pueblo!

La aurora despuntaba lentamente sobre los extensos cañaverales de la hacienda, y la joven esclava Inácia, de mirada profunda, dejaba…

La ama que dominaba y llevaba a su esclavo al límite, no te lo vas a creer.

Aquella mañana de sol abrasador, cuando el canto del sabiá aún resonaba en los cafetales de Vassouras, el destino de…

La ama fue sorprendida en los aposentos de los esclavos con un esclavo a medianoche: su castigo conmocionó a todos ese día.

En Abaeté, Minas Gerais, en el año 1868, la ciudad respiraba una tranquilidad engañosa. Era una región de prósperas haciendas…

El hermano esclavo que vendió a su hermana para salvar su vida: el trato que los destruyó a ambos, Bahía 1856

Era el año 1856, en la ciudad de Salvador, capital de la provincia de Bahía. La ciudad era un violento…

Esclava ALBINA COLGÓ al HACENDADO por los HUEVOS y las CONSECUENCIAS fueron BRUTALES

La Rebelión de Sharila Sharila era una paradoja viviente. Nació afroxicana en el Veracruz de 1827, pero su piel era…

End of content

No more pages to load