Lo llamaban “simplemente un observador” —hasta que ordenó el despliegue de artillería en su propia posición

December 1944, Summer Colonia, Northern Italy. >> A German counterattack is pushing into a village held by a thin American force that’s already being peeled apart. This isn’t a clean fight with a front line and reserves. It’s a collapse in progress scattered positions, broken sight lines, and a withdrawal that’s one mistake away from becoming a route.

Up in an observation post, First Lieutenant John R. Fox is still on the radio. Fox isn’t an infantry officer. He’s a field artillery observer. The man who turns what he sees into coordinates, >> then turns coordinates into firepower. In most units, that job gets labeled support.

In the wrong unit, especially a unit already fighting for respect, an observer can be treated like a passenger. But right now, Fox is the only reason the Americans still have a way to hit the German advance before it reaches them. Here’s the core problem. The Germans are closing distance fast enough to neutralize American advantages. At long range, artillery can break up an attack.

At short range, artillery becomes a liability because every adjustment that brings shells closer to the enemy also brings shells closer to your own troops. And in a withdrawal, friendly positions shift constantly. A coordinate that was safe 5 minutes ago can become fatal now. That’s why artillery doctrine exists.

It’s not theory, it’s damage control. A forward observer can call fire danger close, but only up to a point. The procedure is built around one assumption. Theobserver is trying to keep himself and friendly troops alive. You can walk rounds in. You can tighten the pattern. You can risk it, but there’s a line you do not cross.

You do not call the guns onto your own location. Fox knows this as well as anyone. He also knows something the men in the streets can’t see any more momentum. A rifle squad can hold a doorway. A machine gun can pin a street. But a battalion level push doesn’t need to win every corner. It only needs to keep moving. If it keeps moving, it turns a controlled withdrawal into a chase if it becomes a chase.

Men get cut off. If men get cut off, the whole unit starts dissolving into survivors. So Fox stays at the observation post while others pull back. Not for drama, for one practical reason. If he leaves, the guns lose their eyes. If the guns lose their eyes, artillery becomes blind, and blind artillery either stops firing or starts hitting friendlies.

As the Germans push deeper, Fox faces a shrinking set of options. He can call fire farther out and watch it miss the decisive point, or he can tighten the impacts and accept the risk. Either way, the clock is running and the distance is closing. That’s when the crazy idea becomes unavoidable. Not a heroic impulse, but a cold calculation.

If the only way to stop the advance is to put artillery exactly where it cannot miss, then the one coordinate that guarantees impact is the coordinate Fox is standing on. In a few minutes, Fox will say something into his radio that will make the men on the other end hesitate because it violates every procedure meant to keep soldiers alive.

And the result will be measured in two numbers. How long the German push stops and how many Americans get out because it stopped. If you want to see what happened after Fox gave that coordinate what the guns did, what it cost him, and why the army would argue over it for decades, subscribed to WW2 Echo stories.

Echo, now back to Fox. Fox wasn’t fighting only the Germans. He was fighting the way the army was built to protect itself from mistakes. A forward observer sits at the front, but his authority runs backward through a chain. He doesn’t fire the guns. He requests a mission. The fire direction center computes it, assigns the guns, and sends the rounds.

That system exists for one reason. Artillery is too destructive to trust to impulse. Every step is designed to slow you down just enough to prevent a catastrophe. On a normal day, that friction saves lives. In a collapsing village fight, friction can kill. The rules are simple on paper. Identify the target, send a grid, fire a spotting round, adjust, then bring the full pattern in.

Each correction tightens the distance between friendly troops and the impact area, but the observer is supposed to maintain a buffer because friendly positions shift. Radios cut out and men mishar numbers under stress. And then there’s the phrase, “Every artilleryman understands without needing it.

” explained danger close. Calling fire danger close isn’t bravery. It’s an admission that the situationist is already bad enough that the safest option is losing. It means you are trading risk for time. But even danger close has limits. The system expects the observer to be pushing fire near friendlies, not onto them.

That is the line Fox is approaching and he knows exactly what resistance it triggers on the other end. Because when an observer asks for impacts too close, the first response is rarely Roger. The first response is verification. Repeat the grid. Confirm the direction. Confirm the distance. Confirm friendly locations. Not because anyone is refusing to fight.

Because the men computing that mission are responsible for every shell that lands. A single wrong digit can erase a friendly position and destroy trust in the entire battery. So if Fox ever says the coordinate he’s considering, he can predict what happens next. A pause, a question, a warning, someone trying to pull him back toward the procedures that keep people alive.

But Fox’s social reality makes that resistance worse. He’s not a famous ace pilot. He’s not a decorated infantry captain everyone already believes in. He’s an observer in the 92nd Infantry Division, a unit carrying the weight of skepticism before it even fires a shot. In 1944, that skepticism wasn’t subtle. It lived in assumptions about competence, about discipline, about whether a unit could be trusted.

When people are ready to doubt you, they don’t need evidence. They just need an opening. That means Fox has less margin for error than other officers. One bad mission doesn’t just hurt men. It confirms prejudice. It becomes a story told upward. And those stories shape what commanders allow the unit to do next.

Fox understands all of that in real time because he can hear the tone in voices, the extra confirmation questions, the careful wording. Even when the men on the other end respect him personally, the system still pushes back harder when the request sounds extreme. So he does what smart observers do when the battle becomes messy.

He builds credibility with steps the system can accept. He doesn’t start with the impossible. He starts with the mission that can’t be argued with enemy movement. Clear approach routes, fire that is close enough to matter, but still within the boundaries that keep everyone calm. He keeps his language tight, his grids clean, his corrections small and controlled.

He makes the chain feel safe because he’s not just trying to hit Germans. He’s trying to keep the guns firing when the fight stops making sense. Meanwhile, the village compresses the problem as American troops fall back. Friendly positions drift. A street corner that was ours becomes nobody’s, then becomes theirs. In that kind of fight, artillery isn’t only destructive, it’s also psychological.

If the Germans believe they can move without punishment, they surge. If they believe every alley is covered by steel, they slow. Slowing them is the only way a withdrawal stays organized. That’s the logic Fox is trapped in. The safer he plays it. The faster the Germans move, the faster they move. The more Americans die, the more Americans die, the less anyone cares whether the rules were followed correctly.

So Fox keeps tightening the circle, mission by mission, forcing the system to accept what it normally rejects. And as the distance collapses, the last resistance he has to overcome isn’t German infantry. It’s the army’s own instinct to stop him from saying the one coordinate that ends the argument. Fox starts with a mission the system can’t refuse.

He gives a grid on the German approach routes close enough to matter. Not so close that the fire direction center has to argue with him. The first rounds come in as spotting fire. Fox watches the impacts, measures the error, and corrects in tight increments. No speeches, no panic, just numbers and adjustments. That calm is the first weapon.

Because the moment artillery lands near a moving infantry push, the push changes shape, men spread out, they slow, they stop using the obvious lanes, even if the shells don’t wipe out the unit. They break the rhythm of the advance. And rhythm is what turns pressure into collapse. Fox pulls the pattern closer. Each correction is a decision made in seconds.

How much risk can you accept to buy how much time? He keeps the requests clean and repeated in the exact way the FDC expects. So they keep firing without hesitation. He’s building trust while the fight is falling apart. More rounds hit. The Germans hesitate again longer this time. Not a retreat, but a pause that matters. A battalion push doesn’t need courage.

It needs motion. Artillery takes motion away down below. That pause becomes distance. Distance becomes order. The Americans pulling back can breathe long enough to move as groups instead of scattered individuals. They can carry wounded. they can avoid being cut off at the next bend. That’s the small win.

Not a victory parade, not a headline demonstrating how many were killed. A measurable shift in the only currency that matters in a withdrawal minutes gained without the line snapping. Fox tightens again. Now he’s close enough that the FDC will feel it. He can almost hear the unspoken question on the other end. How close are your friendlies? Because every correction shrinks the buffer that keeps artillery from becoming friendly fire.

Fox answers with control, not emotion. He keeps the adjustments small. He keeps the language precise. He stays inside the procedures just enough that they keep sending rounds because if the battery pauses to debate. The Germans regain momentum immediately. Then he sees the next problem. The Germans aren’t only advancing, they’re adapting.

They start probing for dead space, angles where Fox can’t keep fire without hitting Americans. They push closer to the same buildings the Americans are leaving, trying to use friendly proximity as a shield. That’s the moment Fox needs proof that his method works under the worst conditions. He gets it. A tighter pattern lands, and the German movement stalls hard men pinned behind walls.

The advance no longer flowing forward. It’s not total destruction. It’s control. Fox is shaping the fight with impacts measured in yards, and the German push is forced to slow at exactly the point the Americans need it slowed. The system holds. The guns keep firing. The adjustments remain accurate. That matters more than any body count.

Because it proves Fox can do the one thing every artillery unit fears most. deliver effective fire when friendlies are close and the situation is chaotic. And that proof buys him something real. The right to be believed when he says the next set of numbers. Because the Germans keep closing the distance between danger close and impossible is shrinking fast, and Fox is running out of space to keep the mission inside the safe margins.

Soon, he won’t be able to tighten the fire any further without crossing the oneline doctrine never planned for. And by then, the only way to stop the advance won’t be to adjust the pattern. It will be to eliminate the pattern’s final uncertainty, his own coordinate. The small win doesn’t last because the Germans don’t need to win a firefight to win the village.

They only need to keep moving. Fox watches them shift tactics in real time. They stop using the obvious lanes where shells are landing. They start using the village itself as armor stone walls, tight corners, short dashes between cover. Every move is designed to do one thing close the distance until American artillery can’t be used without killing Americans.

That’s not bravery. That’s experience. And it works. Because the closer the Germans get, the less room Fox has to keep doing what just bought the Americans time. Danger close isn’t a heroic label. It’s a math problem with a shrinking margin. The margin is the buffer between friendly troops and impact points.

That buffer is disappearing minute by minute as the Americans withdraw and the Germans push into the same streets. Fox keeps calling missions. But now each adjustment is harsher. The impacts are tighter. The corrections are smaller. He is squeezing a moving target in a village where everything blocks line of sight. He’s doing it while friendly positions are shifting and communication is fragmenting.

And the battlefield is starting to do what it always does under pressure. Isolate people down below. Squads lose contact with each other. Men fall back in pairs. Someone takes a wrong turn, ends up on the wrong side of a wall, and suddenly the friendly line is no longer where anyone thought it was.

The map still shows rectangles and grid squares, but the reality is bodies moving through narrow streets with only partial information. Fox is still getting information, bits of it, from what he can see and what he can hear over the radio. But the picture is degrading. He can’t guarantee exactly where every friendly is anymore. He can only guarantee where the enemy is pressing because the enemy pressure is loud and obvious.

That asymmetry is deadly for artillery. The system behind Fox senses it too. The fire direction center can feel how tight the missions have become. The tone changes. More confirmation, more cautious repeats. Not a refusal, something worse. The beginnings of hesitation. Fox can’t allow hesitation. If the guns pause, the Germans surge.

If the Germans surge, the withdrawal becomes a chase. And if it becomes a chase, the Americans lose control of who gets out and who gets cut off. So Fox does what he’s been doing all day. He keeps the chain confident by staying disciplined. He speaks in grids, not emotion. He gives corrections that sound like someone who still owns the map, even when the map is slipping away from reality.

But now the Germans are close enough that the mission stop being helpful and start being decisive. This is no longer about slowing the enemy at the edge of the village. It’s about preventing the enemy from breaking through the village and rolling directly into the Americans trying to reform their line.

Fox watches a group of Germans push into positions that if held will let them cut off the retreat route. It’s the kind of move that turns a withdrawal into encirclement. If they take that ground, Americans aren’t just falling back. They’re being boxed in. Fox calls fire. The impacts land close. Too close for comfort, but close enough to deny the ground.

The Germans hesitate again, hugging cover, delaying their own move. Fox tightens the adjustment to keep them pinned. Every correction is a bet that friendly troops have cleared the area behind the impact zone. That bet gets harder to make with every minute because Fox is no longer operating with a friendly line. He’s operating with friendly absence.

He’s trusting that the withdrawal has carried most Americans out of the danger area. He’s trusting that stragglers aren’t hiding behind the exact stone wall the Germans are now using. He’s trusting that the last voices he heard on the radio are already gone. This is what escalation looks like in artillery work, not bigger explosions, smaller margins.

Then the village fight compresses again. The Germans push to within a distance where Fox can no longer separate enemy position from his own position by enough yards to keep the system comfortable. The advance is now pressing into the same blocks of buildings that sit under his observation point. He can see movement where he shouldn’t be seeing it too close, too fast.

Fox’s options narrow to three, and none of them are good. Option one, stop calling artillery. Let the Germans move freely. That guarantees the advance keeps momentum and turns the withdrawal into a chase. Option two, keep calling fire just outside the closest danger zone. That might slow them, but it also gives the Germans room to adapt and keep sliding forward.

It buys seconds, not minutes. Option three, tighten fire into the one place the Germans can’t avoid. The one place that forces a full stop. But that one place is now overlapping with the position Fox is still occupying. This is where doctrine collapses into reality. The manuals assume the observer can pull back with the line.

They assume he can continue adjusting from a new position. They assume the observer survives. Fox has chosen to remain because the guns need eyes. Now the cost of that choice has arrived. Because in order to keep the Germans from cutting off the Americans, Fox has to bring the artillery in tighter than the system was built to accept.

And the only way to do that without guessing, without risking friendly positions he can no longer confirm, is to remove the uncertainty entirely, to use a coordinate that doesn’t shift, his own. Fox keys the radio again. At first, he does what he has done all day. He requests fire as close as the system will tolerate without immediately refusing him.

He wants the chain already moving. He wants shells already in flight. He wants the battery committed to the fight, not paused in debate. Then he makes the transition that changes everything. He gives a correction that tightens the impacts to a point that will make the other end freeze, not because they don’t believe him, because what he’s about to ask violates the deepest rule in artillery work.

Don’t become the target. There will be a warning. There will be a voice telling him it’s too close. There will be someone trying to protect him from himself. Fox already knows that. That’s why he has been building trust with every controlled mission before this. That’s why he stayed calm when the village was collapsing.

That’s why he made the guns hit exactly where he said they would. Because now he needs the battery to do something that sounds insane, but is brutally logical. He needs them to drop steel on the one point that guarantees the German push stops whether Fox lives or not. And when Fox finally says the coordinate, it will not sound like a man trying to die.

It will sound like a man doing his job to the end. Fox had been tightening the circle for so long that the next correction wasn’t really a new tactic. It was the end of the same equation. The Germans were inside the village deep enough that friendly area and enemy area were no longer separated by streets. They were separated by seconds.

Fox could still see movement. He could still read the pressure. But he could no longer guarantee where every American was not perfectly not the way the system demanded. And that’s what forced the final decision. If he kept the shells just outside the closest danger zone, the Germans would keep sliding forward. They’d use the lull between salvos to move.

They’d push to the next wall, the next corner, the next blind spot. That kind of advance doesn’t look dramatic. It just keeps happening until someone finds himself cut off. Fox understood the consequence in plain terms. If the Germans kept their momentum, the Americans below wouldn’t simply fall back. They’d be caught caught while moving, caught while reorganizing, caught while carrying wounded, caught with their backs turned.

So Fox did the one thing that removed uncertainty. He called the next adjustment onto his own coordinates on the other end of the radio. The reaction was immediate because it had to be. A fire direction center can accept danger close. But this wasn’t danger close. This was an observer turning himself into the aim point. It wasn’t merely risky.

It broke the purpose of the rules. The men at the guns didn’t want to do it. Not because they were scared, because they were trained to prevent exactly this moment. They warned him. They questioned the correction. They tried to slow the request long enough to protect him. Fox didn’t give them room. He repeated the grid. He made it unmistakable.

He confirmed it in the simplest language the system couldn’t reinterpret. He stripped away every opportunity for a bureaucratic pause because a pause was exactly what the Germans needed. Then he did something that matters in a story like this. Even if no one watching thinks about it, Fox kept his voice steady.

A steady voice tells the system you’re not confused. It tells the other end you’re not guessing. It tells them you know what you’re asking and you’re taking responsibility for it. That steadiness is what turns an impossible order into an order that gets obeyed. The battery committed. Shells were already in the pipeline now. Steel in flight that couldn’t be called back.

the village, the Germans, Fox’s post. All of it was suddenly under a countdown only Fox could feel, not in seconds on a clock, but in the spacing between impacts. The first rounds hit close enough to confirm what Fox already knew he had chosen the only coordinate that couldn’t drift.

The German push, so confident a minute earlier, stuttered. Men who had been using walls as cover found that walls didn’t matter when the blast landed behind them and the fragments came sideways. The lanes that had been safe became traps because the artillery didn’t care which street you chose. It turned the whole center of gravity into a kill zone.

Fox stayed on the radio long enough to keep it centered. That’s the part most people miss. Calling fire on yourself isn’t one moment of courage. It’s a sequence. The first impacts don’t end the danger. They prove the line is working. The danger ends only if the observer holds the fire in place long enough to do its job to break momentum, to force the enemy to ground, to deny movement for more than a few breaths.

Fox held it down below. Americans still moving out of the village felt the change immediately. The sound of artillery landing where it shouldn’t be landing told them the same thing Fox was trying to buy time. It forced the Germans to stop pushing and start surviving. And in war, when the attacker is forced to survive, the defender is given space to escape.

The German advance didn’t lose because of a heroic speech. It lost its rhythm because the ground it needed was suddenly uninhabitable. And the Americans used that break the only way a withdrawing unit can by turning seconds into distance and distance into regrouping. Fox’s final fire mission was not designed to win the village back.

It was designed to prevent the worst outcome, the one where a retreat turns into a wipeout. In pure battlefield logic, it was an exchange one position. One man traded for the ability of the larger unit to get out intact enough to fight again. The barrage continued. The impacts tightened. The window for survival closed. And then Fox’s voice stopped.

What the guns did next wasn’t controlled by instinct or emotion. It was controlled by the last correct data Fox had given them, the last correction he had insisted on, the last responsibility he had taken. When the fire lifted, the German push had been forced into a full reset movement shattered, coordination disrupted, momentum broken at the exact moment it was about to spill out of the village and into the Americans withdrawing.

That was the decisive fight. Not a bayonet charge, not a last bullet. A man with a radio forcing an entire advance to hit pause at the highest possible cost, because that pause meant the difference between a unit escaping and a unit being swallowed. And only later would the army have to answer the hard question that follows decisions like this.

If an observer can stop an advance when everything else fails, why did it take so long for anyone to admit what he did when the guns finally lifted? It didn’t feel like a clean victory. It felt like a sudden break in pressure, like someone had slammed a door on an advancing wave. The German push into Summer Colonia didn’t disappear. It stalled.

Movement that had been steady turned cautious. Units that had been pressing forward were forced flat, fragmented, and out of rhythm at the exact moment they were close enough to turn an American withdrawal into a chase. That timing is what Fox bought. When US troops were able to reorganize and move back into the village area, they found the cost written into the ground.

Fox’s observation post was no longer a position anyone could hold. Fox was dead near the location he had used to direct the final fire mission. And then there was the number that explained why the German advance had stopped accounts tied to Fox’s official recognition describe around 100 German soldiers killed in the bombardment centered on his coordinates.

That figure isn’t important as a score. It’s important because it shows what artillery does when it hits the exact center of an infantry push at close range. A battalion level advance doesn’t stop because it loses a few men. It stops when the ground it needs becomes unlivable and its forward elements can’t move in coordination anymore.

Fox didn’t need to destroy an entire force. He needed to break momentum long enough for Americans to escape, regroup, and set a new line. Within days, that time paid off. American forces counteratt attacked and the village was taken back by early January 1945 proof that minutes bought can turn into ground regained when a retreat stays organized instead of collapsing.

What Fox demonstrated brutally and permanently was a form of battlefield control that doctrine doesn’t like to talk about directly. Sometimes artillery isn’t about eliminating targets. It’s about denying decisions. He turned his own position into the fixed point that removed uncertainty from the mission. In artillery terms, it functioned like a lastditch protective fire.

Make one piece of ground impossible for the enemy to occupy at the critical moment. Even if that ground is where you stand, the system is built to prevent that request. Fox used it because the situation had already crossed the line where safe procedure could save anyone. And then came the second truth, the one that took decades.

The battlefield understood what he did immediately. The institution took longer. His recognition was delayed, revised, and only later elevated to the level his action had earned. John R. Fox didn’t live to see what his last transmission did to the people behind him. That’s the hard part of stories like this. The battlefield outcome is immediate.

The human accounting comes later. In the days after Summer Colonia, the army moved on the way armies always do. Next ridge, next village, next problem. But Fox’s choice stayed behind in a different way. It became one of those quiet, brutal examples instructors reference when they talk about what artillery really is.

Not just destruction, but control. When everything gets compressed, when units are withdrawing, communications are breaking, and the enemy is close enough to use your caution against you. An observer is sometimes the only person left who can still see the fight as a whole. Fox proved that the man with the radio can carry the weight of the line.

His story also exposed a second truth. Courage isn’t always the dramatic kind. Sometimes it’s the disciplined kind, the kind that speaks in grids and adjustments while the situation is collapsing. Calling fire on your own position isn’t a single heroic moment. It’s the willingness to accept the full consequence of a decision because you’ve calculated what happens if you don’t make it.

And then there’s the legacy that doesn’t doesn’t belong to tactics at all recognition. Fox served in a unit that fought under a cloud of doubt long before the Germans arrived. Decades passed before the institution fully caught up with what the battlefield already knew. When his actions were finally honored at the highest level, it wasn’t just about one officer.

It was about correcting the record and refusing to let the support roles or the overlooked units disappear into footnotes. That’s the lesson Fox leaves behind. Some battlefield decisions aren’t measured by survival. They’re measured by what they prevent. Panic, collapse, encirclement, annihilation. One man can’t stop a war, but one man in one position can stop the worst outcome in front of him.

If you want more true what stories like this, stories where a single decision under pressure changes the outcome, subscribe to WW2 Echo Stories. And if John R. Fox’s last call hit you the way it hits us, drop a comment. Where are you watching from? And what do you think you would have done with that radio in your hands?

News

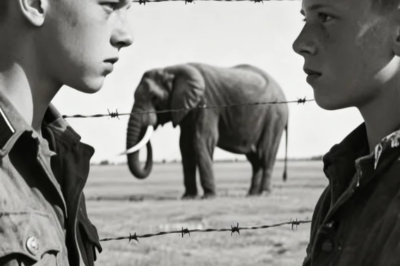

Niños soldados alemanes se fugaron de un campamento en Oklahoma para alimentar a los elefantes del circo ambulante.

Niños soldados alemanes se fugaron de un campamento en Oklahoma para alimentar a los elefantes del circo ambulante. 12 de…

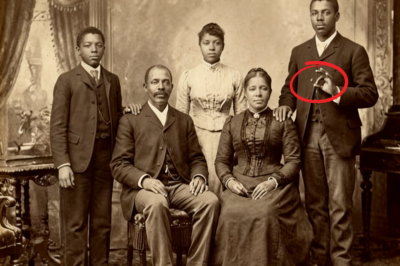

Este retrato de 1895 guarda un secreto que los historiadores nunca pudieron explicar, hasta ahora.

Este retrato de 1895 guarda un secreto que los historiadores nunca pudieron explicar, hasta ahora. Las luces fluorescentes de Carter…

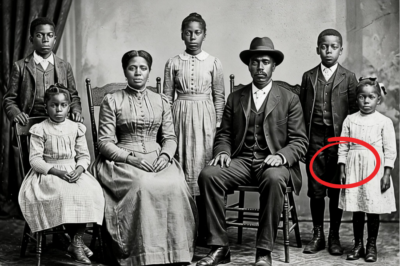

Los expertos pensaron que esta foto de estudio de 1910 era pacífica, hasta que vieron lo que sostenía la niña.

Los expertos pensaron que esta foto de estudio de 1910 era pacífica, hasta que vieron lo que sostenía la niña….

Era solo una foto de estudio, hasta que los expertos descubrieron lo que los padres escondían en sus manos.

Era solo una foto de estudio, hasta que los expertos descubrieron lo que los padres escondían en sus manos. La…

“Estoy infectado” – Un joven prisionero de guerra alemán de 18 años llegó con nueve heridas de metralla – El examen sorprendió a todos

“Estoy infectado” – Un joven prisionero de guerra alemán de 18 años llegó con nueve heridas de metralla – El…

Cómo la bicicleta “inocente” de una niña de 14 años mató a decenas de oficiales nazis

Cómo la bicicleta “inocente” de una niña de 14 años mató a decenas de oficiales nazis Un banco de un…

End of content

No more pages to load